Cypherpunks were keenly aware of how radical their ideas are and how leaving traces that could compromise their privacy could paint a target on their backs. But, they did allow one of them to write about the inner teachings of their movement — it was Timothy C. May, the mad cypherpunk scribe who founded the cypherpunk movement and a vocal advocate for the freedom of anonymous sharing of information online, in particular, that concerning digital money, intellectual property, and government secrets. He was the one who chronicled the cypherpunk ideas and saw the looming horror in humanity’s digital future, calling on people to rise up and resist surveillance unless they want to be controlled and dominated by digital forces beyond their understanding. Timothy C. May presented cypherpunk ideas in two seminal texts:

- Crypto Anarchist Manifesto

- Cyphernomicon

The former is a short summary of why cypherpunks exist; the latter is a sprawling text that goes into excruciating detail as to which obstacles could jeopardize their agenda. Combined, the two texts provide a comprehensive overview of the organization and functioning of cypherpunks from their founding until 2003, which was the last time Timothy C. May updated the latter. Equal parts fascinating, terrifying, and confusing, they are a lasting testament to the cypherpunk brilliance and a haunting reminder that, despite our best efforts, the dreadful vision of overwhelming digital tyranny may still come true. Other texts Timothy wrote about cypherpunks are:

- Libertaria in Cyberspace

- A Crypto Glossary

- Crypto Anarchy and Virtual Communities

- Cyberspace, Crypto Anarchy, and Pushing Limits

Timothy drew heavy inspiration for his writings from two books that he recommended to everyone interested in cypherpunk ideals:

- “Ender’s Game” by Orson Scott Card

- “True Names” by Vernor Vinge

They both depicted electronic societies that had elements cypherpunks thought desirable in our society, such as online anonymity and digital reputation building. Both novels also depicted humans fusing with technology and using their digital prowess to wage war against non-human threats that cannot be defeated by conventional means.

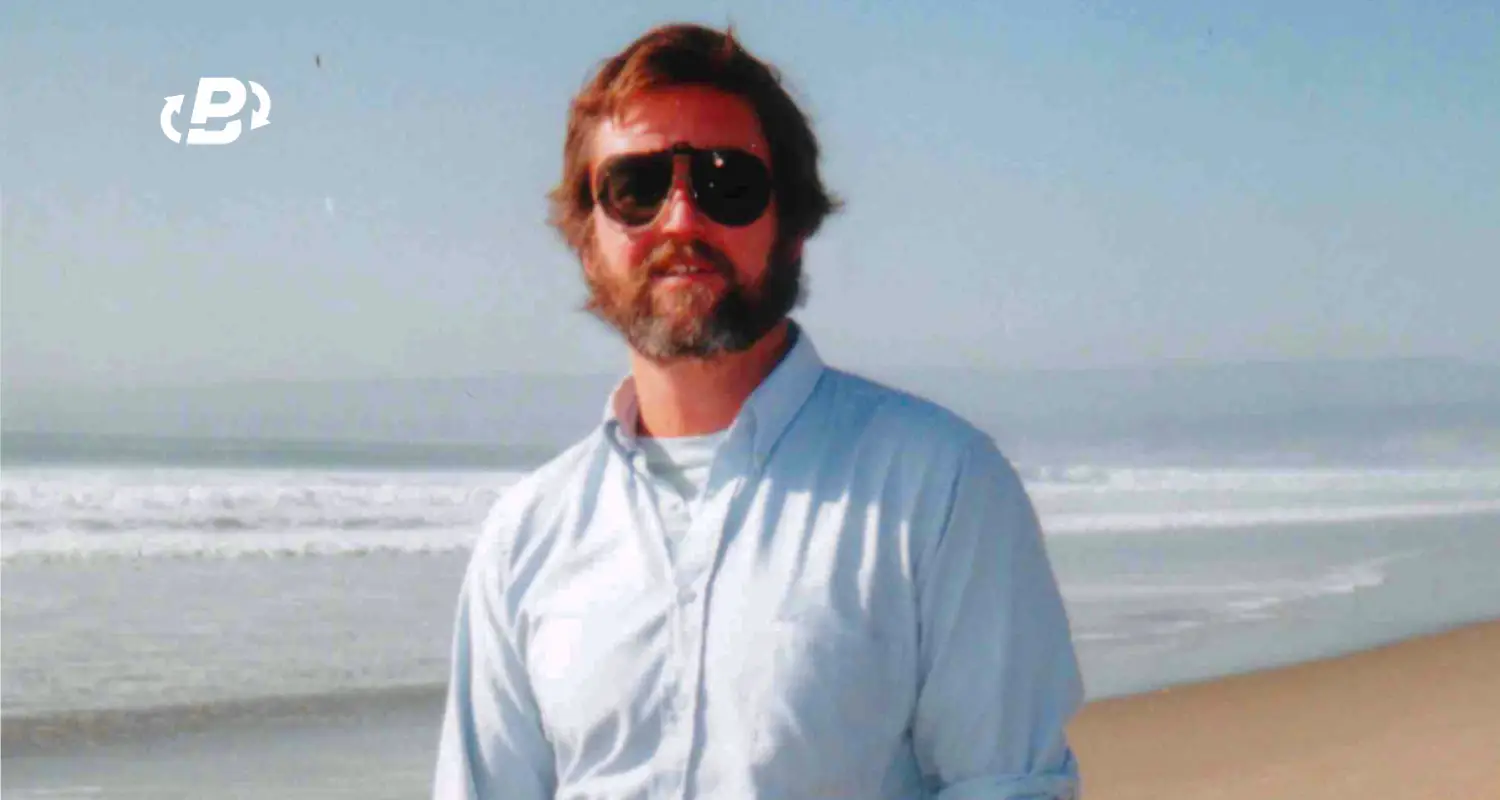

Early life and career

Born in 1951, Timothy C. May graduated from the University of California in 1974 with a physics bachelor degree. He started working at Intel on solid-state physics, eventually ending up in the Memory Products Division, where he discovered the impact of radiation on memory components. He found that alpha particles, the product of radioactive disintegration, hold a lot of energy that could damage the memory components. In a sense, alpha particles are anarchy manifest when they erase the machine’s memory. A machine would normally remember forever — digital information, once stored in its memory, can be duplicated and passed on in perpetuity, but the alpha particle represents total chaos that upsets that status quo, much like anarchists do. Timothy C. May retired at 34. He gathered several awards for his alpha particle work and was wealthy enough from the Intel stock options to dedicate himself to his one true hobby: writing. He started writing a sci-fi novel but never finished it. Out of the works he did finish and publish, the most notable came in 1988, when he published the Crypto Anarchist Manifesto online. The second one, Cyphernomicon, followed in 1994. Cypherpunks believed that everyone could write code, but Timothy apparently did not put much faith in software, focusing on hardware as the deciding factor. He also believed in other forms of hardware for protection, arming himself and sweating bullets as he expected federal agents to bust his door down at any moment. That did not happen; he passed away in 2018 of natural causes at the age of 66.

The first text — Crypto Anarchist Manifesto

The 500-word manifesto, published in 1988, details how computer technology can be used to break away from the government surveillance system. The emphasis is on hardware (chips, satellites, smart cards) that will create an alternate internet, one where anarchy dominates, and which is dubbed “CryptoNet.” Timothy predicts it will become infested by criminal and rogue elements spreading chaos across it, but that will not stop the technology. Governments will try to stop or slow down the spread of technology and control CryptoNet by installing what the Manifesto calls “barbed wire fences.” Cryptography to the rescue, as it will serve as wire clippers that will let people break free and roam the land. The underlying CryptoNet hardware will include encrypted and tamper-proof boxes, the use of which will be equivalent to freedom of speech. Governments will find any number of reasons to limit CryptoNet. Some of those reasons will be valid, but CryptoNet will still revolutionize digital communication just like the printing press did with written communication. Users of CryptoNet will be governed by their own reputation system, which will have even more weight than the credit rating system and which will fundamentally change the nature of government taxation and information control. The text ends with an emphatic call to rebellion, urging people to take up the wire clippers and bring down the barbed wire that’s surrounding them.

Comparison to A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto

Five years later, cypherpunks’ Eric Hughes will publish a more level-headed form of the Crypto Anarchist Manifesto, one that emphasizes privacy, and dub it “A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto.” It will present cypherpunk ideals in a way that is easily understood by the average reader who has no clue how a computer works or why cryptography matters. This manifesto reads like a polished press release and is undoubtedly designed to improve the public image of the cypherpunks rather than make them seem dangerous or elitist. It ends with an understated call to action: “onward.” There is nothing provocative or incendiary in A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto. The strongest expression is that cypherpunks “deplore” cryptography being regulated by governments. There is talk of building new systems to connect people, like in the previous manifesto, but there is no mention of assassins or drug dealers. Instead, the reader is asked to think about privacy and protecting one’s personal identity by using anonymous systems. This sanitized presentation of cypherpunk ideals is certainly more palatable for public consumption, but it does lack some spiciness found in Timothy’s Manifesto. An interesting revelation in Timothy’s Manifesto is that all US and European academic conferences related to CryptoNet are surveilled by the NSA. Conferences were the ideal way to disseminate information, which also made anyone attending them a prime target for surveillance and disruption. That likely caused a great deal of worry and paranoia among cypherpunks, prompting them to create and deploy hardened communication systems to protect their privacy. The next logical step was to create a public knowledge base where anyone could get more information on what to do to further the cypherpunk agenda without being exposed. That task was taken up by Timothy C. May.

The second text — Cyphernomicon

This 163,000-word text arguably represents Timothy C. May’s magnum opus. It is written in red font on black background, first published in 1994 and last updated in 2003. Timothy kept expanding the text with his thoughts, disclaimers, FAQ sections, and instructions on how to find more information throughout the years. It forever remains at version 0.666, with the inspiration for the name coming from H. P. Lovecraft, a horror writer, who imagined a terrifying book called “Necronomicon” that can summon cosmic horrors. The intention is clear — this is a text meant to alienate and frighten the reader. There are no handy summaries or friendly interlinking here; the reader has to toil for morsels of info. Cyphernomicon consists of 20 sections that are barely organized and mostly incomplete. Most of its content is in the form of fragmented sentences that lack interpunction or context peppered with links and email addresses. While it is possible to find Cyphernomicon as single-page text to more easily search through it, the original was broken down into bite-sized morsels of text that the reader had to laboriously click through, perhaps to make it more arcane.

This is Wikipedia before Wikipedia, written before advanced word processors, search engines, or strong hardware, designed to reveal its mysteries only to the most persistent. So, what is the content about? The topics revolve around cryptography and its practical applications as envisioned by cypherpunks, such as digital privacy and digital cash alongside a reputation system that does not involve the government or a person’s real identity. A major motif is that willing participants should have the freedom to bypass any digital conventions they choose. Instead of relying on third parties, such as the government, Alice and Bob should be able to communicate and transact digitally without having to jump through hoops or get what Timothy later dubbed “the Internet driver’s license.” There is a strong sense of paranoia in the Cyphernomicon. In section 17.11.2, Timothy references the 1992 Ruby Ridge incident as well as the 1993 Waco siege, two high-profile cases in which the US government crushed domestic isolationists, homesteaders, and anarchists with overwhelming force. But, he is adamant that there is not going to be a “Waco in cyberspace,” because crypto-anarchists make sure to leave little trace of their activity online. Instead, attacks will come in the form of reputation damage and oppressive legislation.

Other texts by Timothy C May

Cyphernomicon gives the impression of being hastily cobbled together. It is poorly edited and most likely never revisited past the initial publication. One crucial hint that indicates Timothy cared little about the Cyphernomicon is the pervasiveness of quotes, which sometimes come from anonymous sources. How much of the Cyphernomicon is actually Timothy’s writing? It’s hard to tell, but we do have some of his more organized writing, including some emails he sent to other participants on the cypherpunk mailing list, that reveal his thoughts and his writing style.

September 1992 — Libertaria in Cyberspace

This 1,300-word essay details attempts by various individuals to acquire Pacific islands and found a new nation on them called “Libertaria.” They invariably faced logistical challenges, such as being recognized as sovereign nations and having free trade with superpowers. Timothy references “Snow Crash,” in which people of the same persuasion tied together dilapidated ships and chunks of garbage to create a floating continent, The Raft, but mentions that wouldn’t be feasible either due to logistical concerns and the threat of sabotage. What is much more reasonable is creating a Libertaria in cyberspace. The digital world doesn’t face the same logistical challenges, and communities may form and organize as they please. Access to them may be limited locally, but they cannot be brought down as long as they are decentralized. In addition, they may hide in plain sight through encryption, such as by encoding their texts into audio noise and storing it on tapes or encoding them into GIF and PICT files to evade detection. Timothy predicted this freedom to organize in cyberspace will only keep growing as technology and encryption advance and become more pervasive in our lives. That will erode the power of governments to tax and coerce their people, perhaps creating the path to true Libertaria.

November 1992 — A Crypto Glossary

This 4,000-word document was first passed around in printed form during initial cypherpunk meetings in September 1992. Due to popular demand, Timothy put it in digital form and sent it out via email to interested readers, noting that there will be no “cypherpunk FAQ,” so people shouldn’t pester him to update the list. Thankfully, he reneged on that promise, providing us with plenty of text and even an MFAQ in the Cyphernomicon.The Glossary contains definitions of 92 terms, such as “digital cash,” which is defined as a protocol for transferring value, not an asset, and one that can do it anonymously. The definition states the purpose of digital cash and digital money systems is to conserve and implement quantities, such as mass, noting that the topic is too large for a single entry. I did a cursory comparison of terms in this Glossary and those in two modern ones (one by CoinGecko and the other by CoinMarketCap) and found zero matches. I did expect the modern direction of cryptocurrencies to be more relaxed, but it shocked me that none of the terms survived the intervening 30 years. In fact, some of the modern cryptocurrency terms appear derived from memes, such as “Flappening,” a humorous name for Litecoin growing bigger than Bitcoin Cash.

April 1994 — Cyberspace, Crypto Anarchy, and Pushing Limits

This 1,400-word text brought up two topics: a) setting up payments for messages, and b) self-governance in cyberspace. The first topic talked about implementations of cryptocurrencies while disregarding practical demands to make them possible. Timothy said the biggest potential implementation is that, just like with any other conventional form of payment, cryptocurrencies could be used for pay-as-you-go transactions. He stated that would be the ideal way to prevent email spam, because then the spam sender would have to pay a small amount of money for each email, just like we already have with postage and physical mail. Therefore, he recommended developing a “digital postage” system as the first and the most obvious way to implement digital cash. That would be followed by the deployment of anonymizing protocols described by David Chaum and a move away from common systems that encourage overuse and abuse. The second topic concerned expanding in cyberspace and who will control it. Timothy mentioned “Snow Crash,” a cyberpunk novel in which cyberspace is controlled by a government that has zoning laws similar to those in physical space, and stated he disagreed with that vision of the future. In his opinion, access to cyberspace equals ownership of cyberspace.

As long as a monopoly on access to cyberspace is prevented, it will be infinitely expandable because there will be an abundance of competitors who will own certain ways to access cyberspace and, by their very existence, prevent centralized censorship or zoning. Timothy said that those two factors combined — micropayments and democratization of access to cyberspace — would make it impossible to track down crypto-anarchists in the future. There won’t be any centralized access rules; anyone will be able to host a portion of cyberspace, doing with it what they will. He predicted that, in the near future, much of our lives, including trade and entertainment, will move to cyberspace to the point there will be no turning back. For that, he said, a strong crypto is a must as the foundation of inviolable cyberspace.

December 1994 — Crypto Anarchy and Virtual Communities

This 5,400-word essay is in many ways an expanded version of the April 1994 text. It goes over the same two topics, but this time explains the role of cypherpunks in both. In Timothy’s view, cypherpunks are the kind of community that can create a cyberspace Libertaria where cypherpunks will enjoy an unfettered flow of digital cash and information. But, it will take time for the digital Libertaria to manifest in the real world. That is because the methods for doing so are still being developed and the people who are supposed to bring about the change are isolated and timid. Timothy is sure that it will happen, one way or another. Cyberspace will interpret any attempt by governments to censor or slow down the change as damage and route around it, finding another outlet for expression.

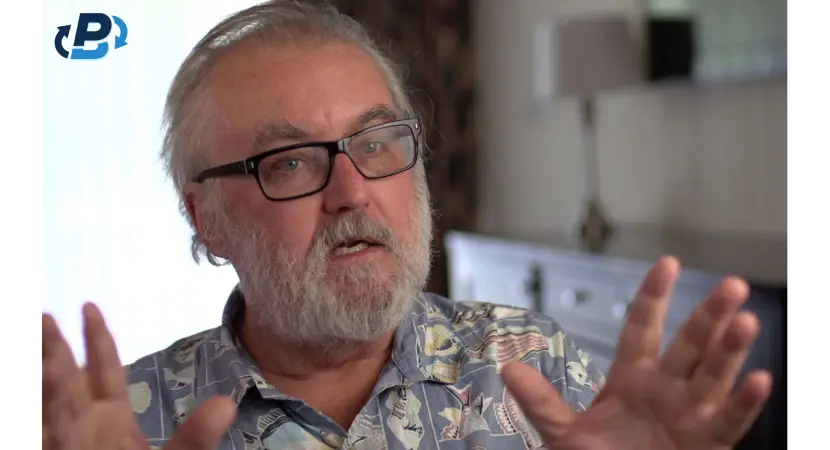

Timothy’s Stance on Cryptocurrencies

Section 12 of the Cyphernomicon dealt with digital currencies. It stated that David Chaum’s ideas on privacy are central to all cypherpunk ideas about cryptocurrencies, especially his stance on buyer privacy being paramount for digital life. In addition, the main problem with cryptocurrencies was that people who want to launch one don’t understand what money is or how it works. Rather than being an asset, digital money should be a transfer mechanism, a “digital check.” In that way, people would stop worrying and quibbling about what digital money is supposed to be and just use it. In one interview before his death, Timothy C. May expressed his frustration with cryptocurrencies trying to become “Yet Another PayPal.” In his view, cryptocurrencies were meant to avoid government regulation, such as the privacy-intrusive KYC (Know Your Customer), not adopt it. Timothy reiterated David Chaum’s ideal of making a monetary transaction system where the buyer’s privacy is protected. That stands in stark contrast to cryptocurrency exchanges that do their best to humiliate their users through intrusive demands for private info. As for Bitcoin, though it did work as described in the whitepaper, Timothy said the overall confusion and chaos around it made it “not really ready for primetime.” He did praise how Bitcoin provided privacy and how it increased public interest in cypherpunk ideas. Still, he lamented the fact there’s little talent in the industry and too much breathless reporting. It all reminded him of hype surrounding other bubbles, such as the dot-com bubble, that had ended in catastrophe.

PlasBit’s Mad Scribe

We dove deep into cypherpunk history and fished out a few shining pearls from the murky depths of Timothy C May’s imagination. He was not just the cypherpunk mad scribe but also a digital homesteader who was in constant fear over his digital existence, perhaps because he realized that defending one’s virtual home makes as much sense as defending one’s physical abode. After all, if we’re going to spend most of our lives online, shouldn’t we treat our online existence as seriously as we treat our physical existence? Timothy certainly did spend most of his life online, investing 30 years in retirement in pursuit of ways to articulate and deploy ideas and systems that would make people truly safe online. Timothy C May spent the latter half of his life in search of good company, people who would help him refine his ideas, but he did not have the luxury of a strong company backing him like I have with PlasBit.

During my work for PlasBit, I’ve been constantly inspired by just how genuine and kind its employees are. They provided me with all the encouragement and resources I needed so that we could succeed and create something completely new, perhaps a Libertaria of our own. Maybe that is why I can confidently call myself “PlasBit’s mad scribe” as I continue detailing cypherpunk ideas and ideals for the world to see. Although PlasBit is a centralized exchange regulated by the Polish government, it is a self-funded company that is genuinely trying to move the needle towards the cypherpunk cyberspace Libertaria. At least as far as my writing is concerned, PlasBit promotes autonomy and privacy, but its internal documents I’ve seen also state the company cherishes private data of its customers and offers non-KYC services to them.